OCEANS

Brazil wants to add a touch of ocean blue to its green agenda

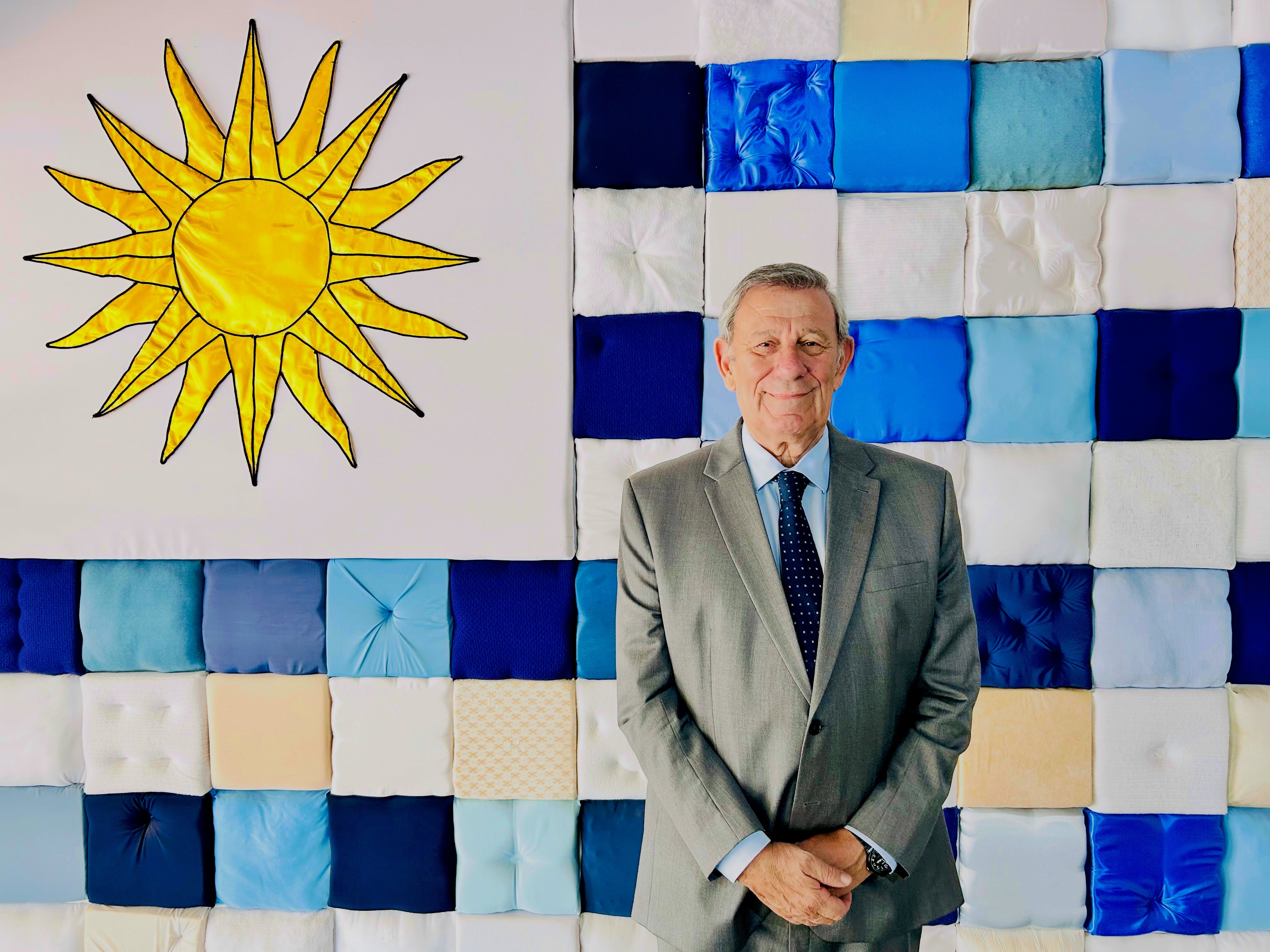

Brazil calls its 3.5 million square kilometers of maritime areas the “Blue Amazon.” Photo: Navy

As Brazil prepares to host the UN Climate Change Conference (COP30) in the Amazonian city of Belém, in November, the country is trying to introduce a touch of blue into its green agenda.

The goal is to draw greater attention to the role of oceans in climate regulation and environmental justice. Two-thirds of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, and the oceans are the planet’s largest carbon sink.

Amid growing international focus on the role of our oceans — shown by the record number of high-level officials attending the UN Ocean Conference in Nice, France last week — the Brazilian government is seeking to position the country at the forefront of the debate, announcing new commitments and proposing fresh international initiatives.

Alongside Belgium, Brazil is preparing to lead discussions at the Ocean and Climate Dialogue event in Bonn, Germany next week. “It will be an important space to develop ocean-related proposals within the COP30 negotiations,” said Ana Paula Prates, head of the oceans department at Brazil’s Environment Ministry.

The country has a lot to say on this matter. Brazil has long prized having more than 3.5 million square kilometers of maritime areas under the country’s jurisdiction, even officially naming this area the “Blue Amazon,” due to its immense biodiversity and geopolitical importance.

The area could get even bigger. Brazil has been engaged for years in a battle at the United Nations to gain recognition of new areas of its continental shelf, which would expand its Blue Amazon to 5.7 million square kilometers. This year, it secured at least part of its claims, along the Equatorial Margin region, off the northern coast.

At last week’s UN Ocean Conference, Brazil and hosts France launched the “Blue NDC Challenge,” an initiative that encourages countries to include oceans in their Paris Agreement climate commitments (NDCs). Governments that accept the challenge may receive support from initiatives such as Ocean Breakthroughs, led by the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action, and the NDC Partnership, coordinated by the World Resources Institute.

At the end of 2024, Brazil explicitly included ocean-based climate actions in its NDC for the first time.

Brazil and France also pledged to develop a maritime corridor aimed at making navigation between the two countries more sustainable, through the use of low- or zero-emission fuels. As previously reported by The Brazilian Report, Brazilian diplomacy has also been pushing for the use of biofuels in global maritime transport.

The attempt to elevate the ocean agenda on the international stage, however, is not without contradictions and delays on Brazil’s behalf. Environmental organizations had already been putting pressure on the Brazilian government to show greater courage and ambition in this regard.

Despite signing it in 2023, Brazil has yet to ratify the UN High Seas Treaty, which addresses biodiversity management beyond countries' exclusive maritime jurisdictions — an area that accounts for half of the world’s oceans. In Nice, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva promised the treaty would be ratified later this year.

Meanwhile, Brazil chose not to sign the Nice Call for Action — a document proposed by France in support of an ambitious treaty against plastic pollution. The abstention is part of Brazil’s push to ensure that the future agreement includes financing mechanisms from wealthy nations to help developing countries reduce plastic production and consumption. It is worth noting that Brazil is a major producer of oil, the raw material used to make plastic.

Oceanographers have raised concerns not only about the degradation of Brazilian waters but also about the lack of systematic data on these ecosystems. The federal government has acknowledged the issue and promised to implement an integrated ocean monitoring system.

In 2024, amid devastating heat waves, Brazil witnessed a historic die-off of its coral reefs — ecosystems that host a large share of marine biodiversity. In response, the federal government recently launched ProCoral, a national strategy focused on reef protection.

President Lula has also reiterated his commitment to increasing the share of effectively protected marine areas from 26% to 30%. Experts note that even the current 26% are not as well protected as they should be, due to management challenges, but the new target aligns with the Global Biodiversity Framework.

Initiatives coming from Brazil’s Congress, however, have done little to strengthen the credibility of the environmental commitments announced by the federal government — with the notable exception of the Sea Law approved by the House last month.

Now headed to the Senate, the bill establishes a national policy for Brazil’s entire coastal and marine system. It requires, for instance, that municipal master plans include guidelines for the protection of these ecosystems.

“When we become too strict, we might end up blocking positive developments,” said Congressman Luiz Lima, referring to the construction of hotels and resorts. Framing environmental protection and economic development as opposing goals has become a hallmark of congressional debate in Brazil.

Recently, for example, the Senate approved a bill dismantling the country’s environmental licensing framework, loosening requirements for a whole host of projects. The Environment Ministry has warned that the bill “poses a risk to environmental and social safety in the country” and “violates the Constitution.” Environment Minister Marina Silva, however, has faced strong opposition — including from within the government itself — particularly due to tensions over offshore oil exploration in the Amazon region.

Even so, Marina has been able to count on strong international pressure. In a context of shifting global power dynamics, especially amid the United States’ growing isolation, President Lula is well aware that aligning rhetoric with action will be essential if Brazil wants to take on a leadership role in climate diplomacy.