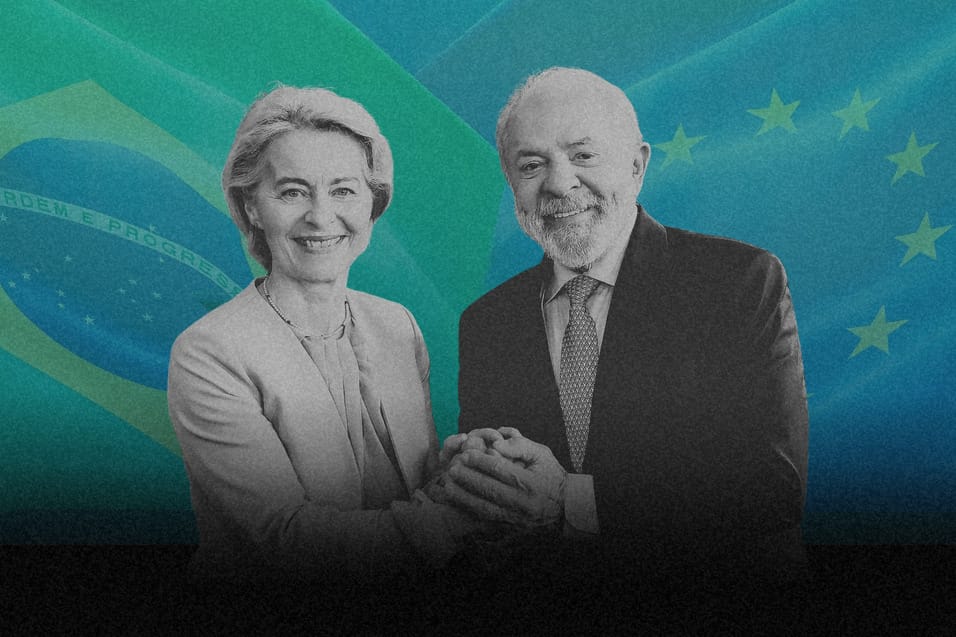

Amid a global context of eroding multilateralism and rising US trade wars, Mercosur and the European Union are trying to create a shared market for more than 700 million people.

The proposed free trade zone for goods and services encompasses 27 European countries, plus Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay on the other side of the Atlantic, with Bolivia in the process of joining as well. Combined, the economies involved in the deal make up for approximately 20% of global GDP.

The deal was finally signed on January 17, after more than 26 years of back-and-forth negotiations.

But yet again, European farming countries are doing whatever they can to stall its implementation. On January 21, European lawmakers backed a resolution to seek an opinion from the EU’s Court of Justice on whether the free-trade deal complies with existing EU treaties.

That could stall the deal by up to two years — although the agreement’s backers, such as Germany, are trying to go ahead and implement it on a provisional basis until the court says its piece.

Across the Atlantic, the Brazilian government wants to wrap up approval of the deal by June, as the country will be focused on the October elections from that point on.

At this point, the Mercosur-EU deal is yet again in a familiar spot of uncertainty. This has been the story for more than a quarter-century: two steps forward, one step back.

Trade liberalization between the EU and Mercosur will be gradual, with some processes needing up to 15 years to take effect — if it ever materializes (and the Europeans keep reminding us that this is one big if).

According to an analysis by the National Confederation of Industry, products in Brazil’s export basket will benefit from shorter timelines for tariff reductions than products exported by the European bloc to Brazil. In other words, Brazil will have more time to adapt.

But it is not just about tariffs. The harmonization of regulatory standards, for instance, encourages foreign direct investment, production chain integration, and the exchange or joint development of technologies.

The trade-off, of course, is increased competition for domestic producers, who throughout the negotiation process sought to secure as many defensive measures as possible.

To understand the balance of forces proposed by the EU-Mercosur agreement and the tools available for Brazilian producers to make the most of it, our guest is the economist Lia Valls, an expert on Brazil’s foreign trade.

She is a senior fellow at the Brazilian Center for International Relations (CEBRI) and a professor at State University of Rio de Janeiro.

The interview was recorded on January 19, about 10 hours before the EU Parliament’s vote that could stall the agreement. In the conversation, Valls unpacked:

Why Brazil trades so little with the world

What the Mercosur-EU deal actually liberalizes

Investment, industry, and the risk of re-primarization

Politics, rules, and the future of multilateral trade