- The Brazilian Report

- Posts

- 🧬 The story told by Brazilian DNA

🧬 The story told by Brazilian DNA

Findings from a new genomic study contain important lessons about Brazil’s past and could have important ramifications for science going forward

HERITAGE

Everyone knew Brazil was racially diverse; a new study took that to a new level

A decade ago, photographer Angélica Dass shot volunteers of different skin tones, and matched a square of 11 pixels from their noses to a corresponding shade in the industrial palette Pantone to expose – and subvert – racial prejudices. Photo: CNI

In 2020, the newsroom of The Brazilian Report ran a modest experiment: we all took a DNA test. As a team covering a country as multifaceted as Brazil, we thought we’d see that diversity reflected in our genes.

Instead, what came back told us something more unsettling — and more profound.

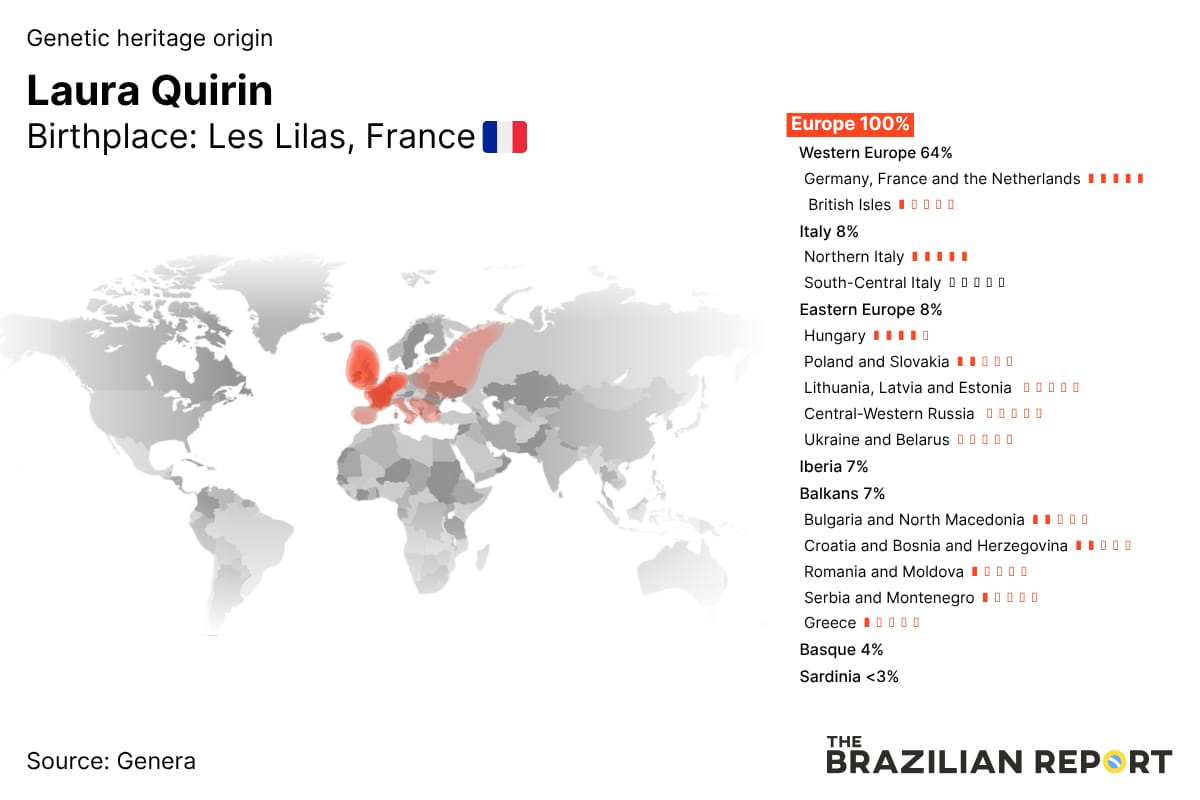

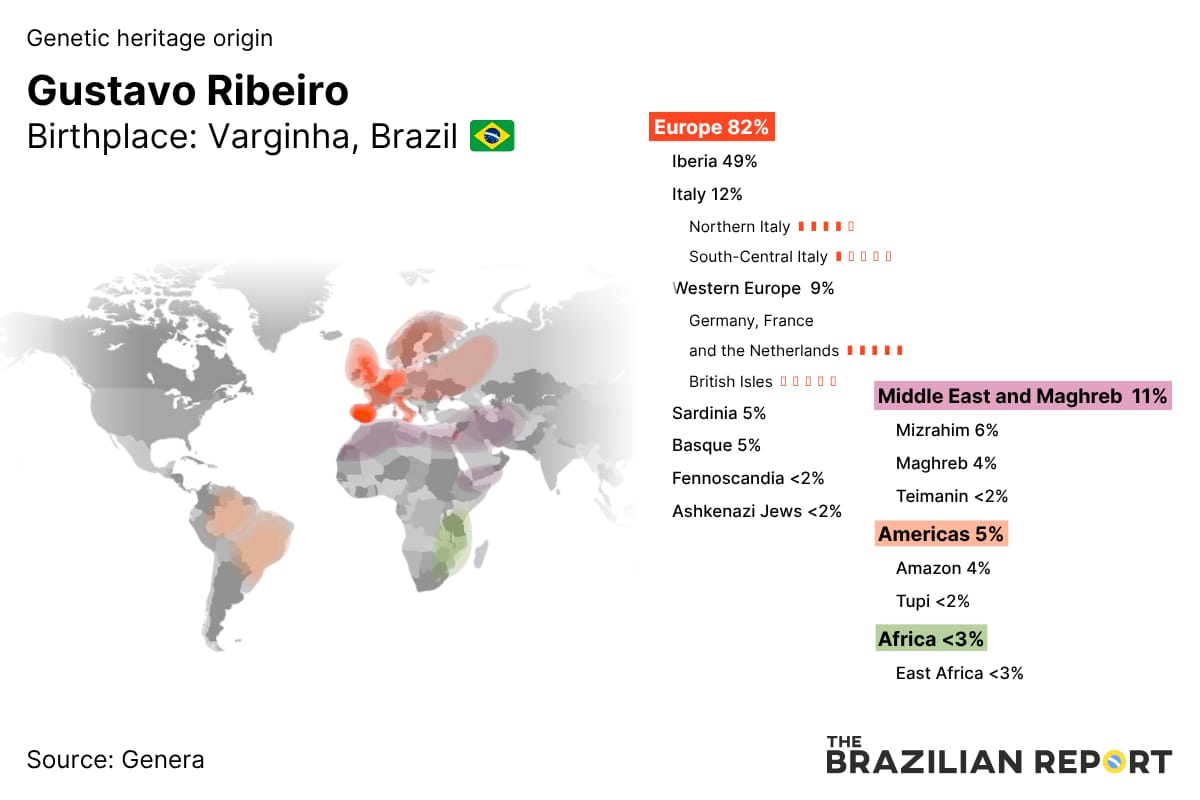

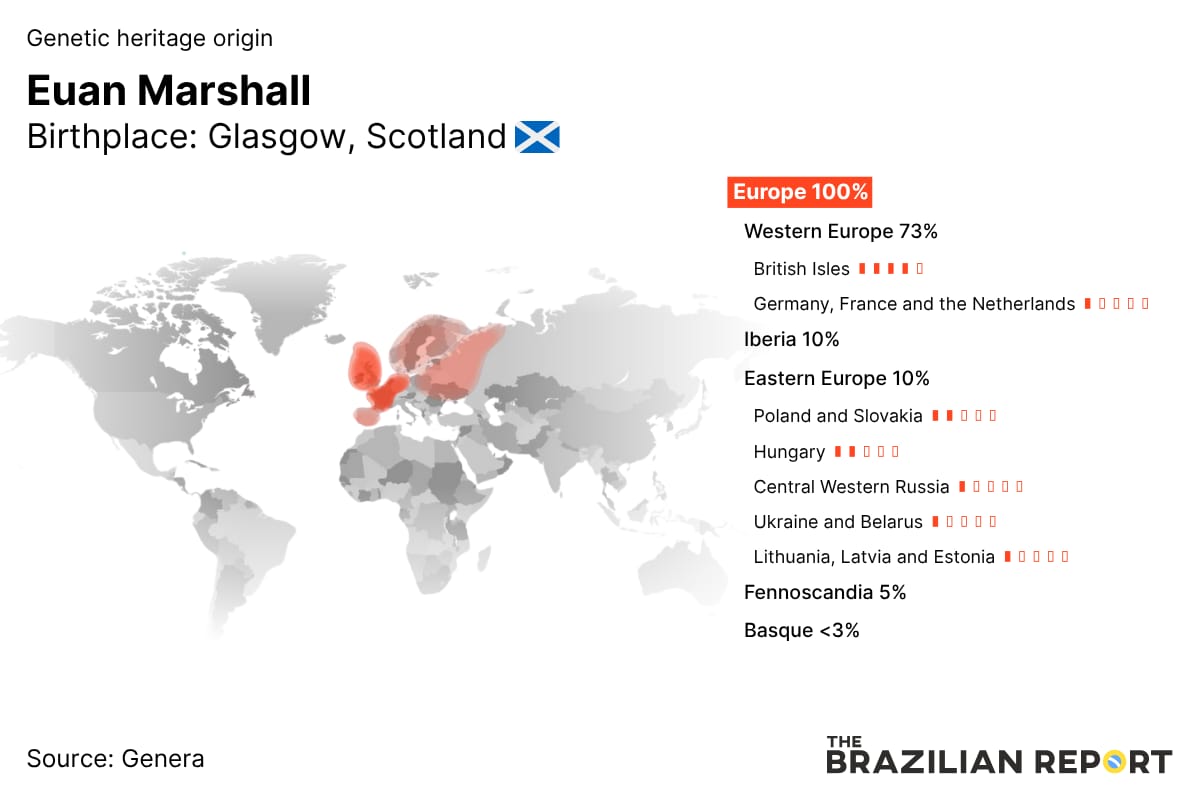

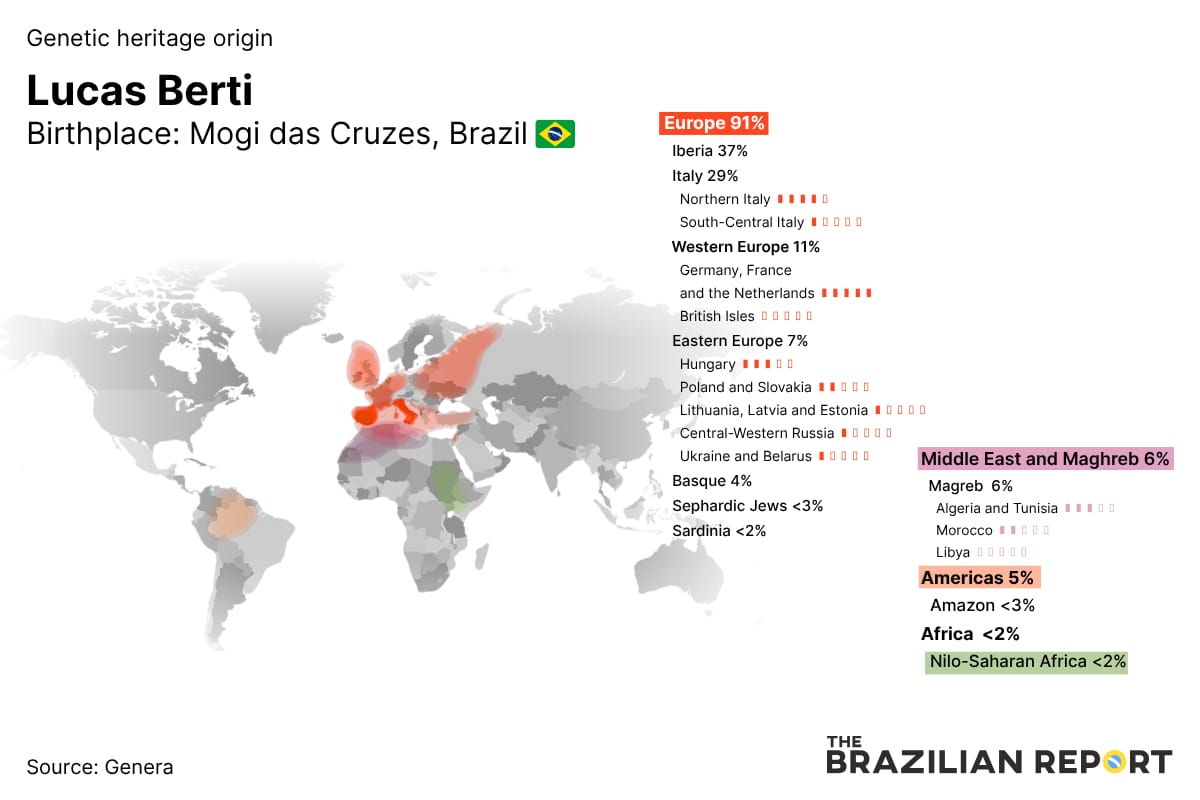

While our team is almost entirely Brazilian, our ancestry skewed overwhelmingly European. Our social condition can explain that: we are college-educated and multilingual, which are often class determinants. Four people who were in the team then remain with us:

I am 82% European; Lucas Berti, our Latin America reporter, clocked in at 91%. Meanwhile, my French co-founder Laura Quirin and Scottish deputy editor Euan Marshall were 100% European. Lucas and I only had 3% and 4% indigenous ancestry, respectively.

In light of new findings published in Science last week, our DNA results feel like a microcosm of Brazil’s enduring inequities.

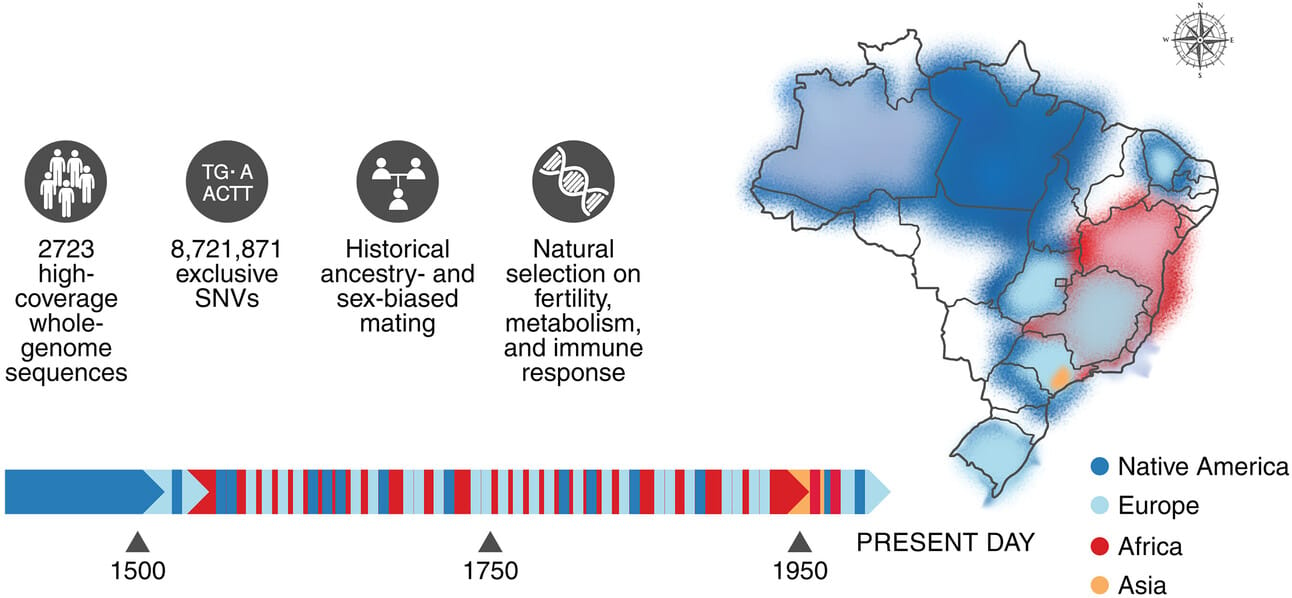

A groundbreaking genomic study sequenced the full DNA of 2,723 people across Brazil, from riverine communities in the Amazon to the industrial cities of the south. What the researchers found is staggering: Brazil is the most genetically diverse country on Earth. More than 8.7 million previously unknown genetic variants were discovered, many potentially relevant to understanding diseases ranging from malaria to obesity.

For decades, Brazil has been largely absent from global genomic research — a blind spot that skewed medical studies toward populations of European descent. But this new research, led by scientists at the University of São Paulo, shines a light on just how rich and complex Brazil’s genetic heritage truly is. And in doing so, it challenges the narratives we’ve inherited from science, from politics, and even from ourselves.

The study confirms what historians have long documented: Brazil’s modern population was shaped by centuries of migration, be that forced or otherwise.

From the 1500s onward, about 5 million Europeans settled in Brazil, largely from Portugal and Italy. At least the same number of Africans were forcibly brought to the country through the transatlantic slave trade (although the illegal slave trade makes the numbers imprecise). Meanwhile, Brazil’s indigenous population — over 10 million strong before colonization — was decimated.

Brazilian genomic diversity. Source: Science

Today, the average Brazilian genome is roughly 59% European, 27% African and 13% indigenous. But that blend is neither uniform nor equal. In the North, indigenous ancestry is higher. In the Northeast, African ancestry dominates. And in the South and Southeast — where our newsroom is based — European heritage takes the lead.

This imbalance is etched into our chromosomes. More than 70% of Y-chromosomes (which trace paternal lineage) are European. In contrast, mitochondrial DNA (which traces maternal ancestry) is overwhelmingly African and indigenous. That disparity reflects a grim historical reality: European men, often settlers or colonizers, fathered children with indigenous and African women — in many cases, through coercion or violence.

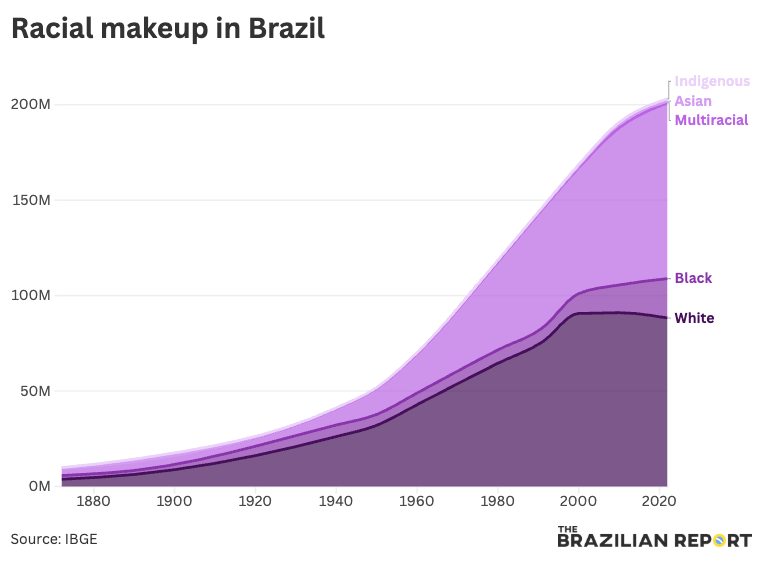

Brazil’s 2022 census marked the first time that multiracial people outnumbered any other group in the country, making up 45% of the total population.

However, some Brazilian statistical nuances must be understood to fully comprehend the significance of this finding. Race is self-identified in the Brazilian census, adhering to four categories: black, white, indigenous, amarela (East Asian), and parda — or multiracial, now the largest contingent in the country.

Taken literally, the term parda refers to a shade of brown, and is used in Brazil to refer to people of mixed indigenous, European, and, above all, African ancestry.

Previously the largest racial group in Brazil, the white population now makes up 43% of the country. Just over 10% identify as black, while the indigenous and amarela populations make up 0.8% and 0.4%, respectively.

Since the 2010 census, the multiracial, black and indigenous populations saw significant increases, the latter growing by almost 90%. The white and ethnically East Asian population, meanwhile, became smaller.

The second important Brazilian nuance is that, despite the significant changes from 12 years prior, the 2022 findings do not necessarily mean the country has undergone a major demographic shift. Instead, they suggest a change in Brazilians’ relationship with their own racial identity.

Though race is self-defined, the country’s complicated and often violent history of miscegenation of indigenous, European and African populations makes it challenging for Brazilians to trace their heritage and determine their ethnicity.

While the study’s historical implications are striking, its scientific ramifications may prove even more important. The researchers found over 36,000 genetic variants with potential deleterious effects — some of which may influence fertility, immune response and metabolic function. In a country still struggling with high rates of infectious disease and chronic illness, understanding these variants could be the key to designing more effective treatments.

Brazil’s unique admixture also presents an opportunity for global medicine. Because its population includes genetic contributions from underrepresented regions — including West Africa, the Amazon and Southern Europe — Brazil’s genomes can help fill gaps in medical research. "We can use this data to better understand the health of people not just in Brazil, but in the ancestral populations that shaped it," said Tábita Hünemeier, one of the study’s lead authors.

For decades, most genetic studies were based on white, wealthy populations in the US and Europe. That skew has real-world consequences: medications, diagnostic tools and even disease risk assessments are often less effective for people with non-European ancestry. Brazil’s genomic diversity could help correct that imbalance, but only if it becomes central to future research.

Our DNA test results at The Brazilian Report were, in retrospect, revealing — but not in the way we expected. They showed how proximity to whiteness, both genetic and social, still shapes opportunity in Brazil.

This new genomic study doesn’t just map genes. It shows how centuries of exploitation left physical imprints on today’s Brazilians — in our health, in our identities, and in our very blood.

QUICK CATCH-UP

📷 Sebastião Salgado, one of Latin America’s most acclaimed photographers and a champion of environmental causes, died Friday. He was 81. Over a five-decade career, he sought to “make people aware that together we can do things differently,” he told AFP last year. His legacy will be featured in Monday’s edition of our Brazil Daily newsletter.

🎬 Kleber Mendonça Filho won best director and Wagner Moura took best actor at the Cannes Film Festival for “The Secret Agent,” a crime drama set during Brazil’s military dictatorship that is already drawing Oscar buzz.

🧩 Brazil’s 2022 census data show that 14.4 million people in the country have a disability — 7.3% of the population aged two and above. The survey also found 2.4 million people diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, representing 1.2% of the population. It was the first time ever that the census accounted for people with autism in Brazil.

⏳ New rules for medical cannabis use were expected this week but have been pushed to September to allow for a broader action plan and wider stakeholder input. Experts say the delay signals the government’s intent to build a more comprehensive and detailed regulatory framework.

✝️ A former Brazilian seminarian is stirring controversy with a new book on the “pulsating gay life” within the Catholic Church. Drawing from personal experience, 33-year-old Brendo Silva describes the institution as “a system of lies, oppression and pretense that locks people in the closet and teaches them to hate people like themselves.”