- The Brazilian Report

- Posts

- 😒 Souring Moody’s

😒 Souring Moody’s

Moody’s glum on Brazil’s outlook. Are Brazilians more optimistic about China than they are about the US? Eduardo Bolsonaro wants to follow in his father’s footsteps and become president

MARKETS

As fiscal challenges mount, Lula gets a warning

Et tu, Lula? Finance Minister Fernando Haddad’s recent tax hike was criticized by President Lula over the weekend during a meeting with lawmakers. Photo: Washington Costa/MF

Moody’s Ratings delivered a cautionary signal to Brazil’s government last Friday, lowering the country’s credit outlook from “positive” to “stable.” While the agency reaffirmed Brazil’s Ba1 rating — still one notch below investment grade — the decision underscores mounting skepticism about the country’s ability to tame its rising debt and regain fiscal credibility.

👉 Why it matters. The downgrade is a setback for President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Finance Minister Fernando Haddad, who have spent much of the past year trying to assure markets that their fiscal framework can hold. In October 2024, Brazil had been awarded a better rating by Moody’s, viewed at the time as an endorsement of the administration’s efforts to restore fiscal discipline. But since then, the economic winds have changed.

In its decision, Moody’s cited the “pronounced deterioration in debt affordability and slower-than-expected progress in addressing spending rigidity,” despite Brazil meeting its primary balance targets.

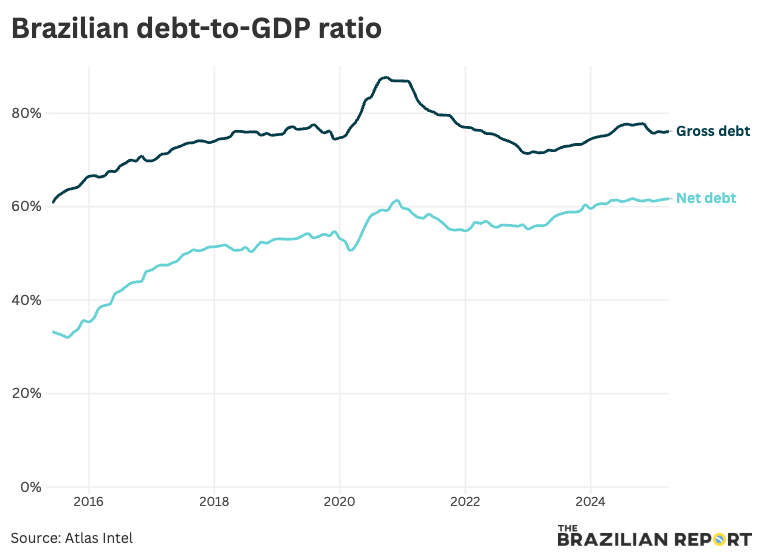

Interest payments are surging, largely due to Brazil’s heavy reliance on inflation-linked and variable-rate debt, which is highly sensitive to the Central Bank’s steep interest-rate hikes. The result: a projected debt-to-GDP ratio of 88% over the next five years, up from 82% just seven months ago.

“The government’s ability to materially reduce fiscal vulnerabilities and stabilize debt burden in the short run remains constrained,” Moody’s analysts wrote. That is a polite way of saying that Brazil’s spending structure, in which welfare and pension benefits are tied to the minimum wage, has left little room for maneuver.

The fiscal situation has become politically fraught. A week and a half ago, the government unveiled a controversial decree raising the IOF financial transactions tax, aimed at plugging shortfalls without congressional approval. But the backlash was swift. Lawmakers are threatening to repeal the hike, forcing Haddad into either finding revenue elsewhere or freezing more budget funds. A partial retreat from the IOF plan has left the fiscal strategy in limbo.

A rollback in Brazil is inevitable — the only question is which form it will take. The most likely target on the chopping block is the recent hike in the IOF tax on forfaiting,1 a type of supplier financing — which the government’s recent decree treats as credit operations.

The swift backlash has reignited a familiar storyline under this administration: the hunt for alternative revenue streams. This week is expected to see the government run several potential solutions up the flagpole. While neither would provide a permanent fix, possibilities include:

Oil royalties: Government sources estimate that adjusting the benchmark pricing used to calculate royalties could yield up to BRL 10 billion reais (USD 1.73 billion). The change depends on a decision by the National oil Agency (ANP), which is expected to vote on the matter by July.

Betting taxes: Haddad and key allies have also floated the idea of taxing sports betting platforms to help offset the IOF hike and broaden the tax base.

BNDES dividends: Another possibility is tapping into dividends from Brazil’s National Development Bank (BNDES). In 2023, the institution transferred BRL 29.5 billion to the National Treasury, and an early payout could serve as a fiscal cushion.

At the heart of Brazil’s fiscal dilemma is a paradox.

On paper, the economy is performing well. GDP grew at an annualized 2.9% in Q1 2025, bolstered by strong agribusiness output and resilient consumer spending. Formal job creation beat expectations in April, and unemployment fell to 6.6%, one of the lowest rates in recent history. Yet it is precisely this strength that has reignited inflationary pressures, prompting the Central Bank to raise interest rates to 14.75% — the highest level in nearly 20 years.

This tightening cycle is taking its toll. Industrial output is slowing, and investment decisions are being deferred. Brazil’s interest-to-revenue ratio is expected to peak near 21% in 2025, nearly six points higher than in 2023. With so much revenue consumed by debt servicing, there is little room left for public investment, undermining long-term growth prospects.

Moody’s did highlight Brazil’s credit strengths — namely, a large, diversified economy with strong external accounts and a robust track record of reform across administrations. But the agency warned that without profound structural changes — such as unlinking social benefits from wage hikes and reducing revenue earmarks — fiscal credibility will remain elusive.

With less than 18 months until the 2026 election, Lula sees little political incentive to choose austerity. Domestic investors have always been sour on the leftist president, but as spending grows, foreign markets — which saw him in a more positive light — seem to be following suit.

GEOPOLITICS

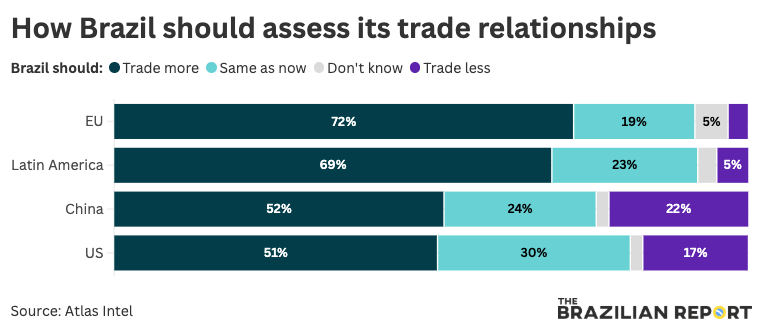

Charts of the week: Brazilians’ cautious China optimism

Chinese leader Xi Jinping during a Nov. 2024 visit to Brasília. Photo: Ricardo Stuckert/PR

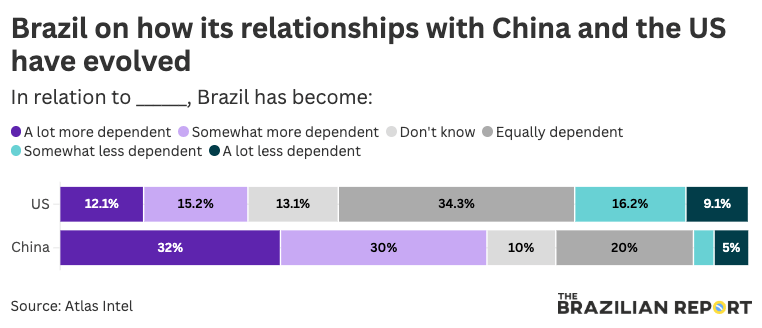

A new survey suggests that ordinary Brazilians increasingly see China as the most important economic force shaping their country, and not the United States.

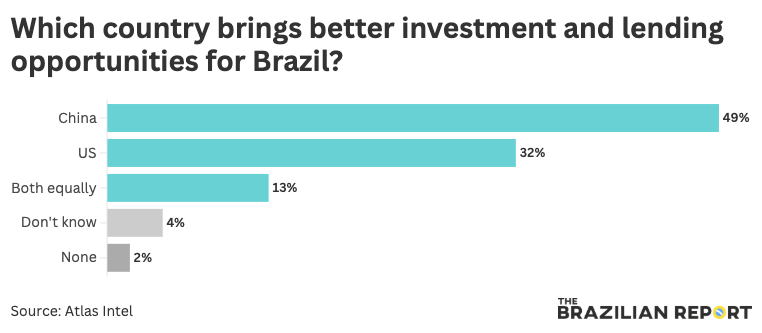

According to the May edition of the Latam Pulse report by Atlas Intel, 58.6% of Brazilians believe China holds more economic sway over Brazil than any other country. Only 23.7% mentioned the United States when asked the same question. A significant chunk of respondents (48.5%) also said China offers better opportunities for investment and financing, compared to 32.4% who said the same about the US.

👉 Why it matters. The data reflect Brazil’s shifting position on the geopolitical chessboard, a trend reinforced by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s high-profile visit to Beijing last month. The trip resulted in more than 30 cooperation agreements and a coordinated development push that in many ways aligns Brazil’s infrastructure agenda with China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

While Brazil has not formally joined the program, the message was unmistakable: the two nations are drawing closer.

Brazilians have long been wary of foreign entanglements, shaped by a historical memory of exploitation, asymmetrical trade and unmet promises.

From the colonial-era extraction of gold and sugar to more recent grievances over predatory lending, intellectual property disputes and environmental pressures from abroad, there is a lingering sense that international partnerships often leave Brazil on the losing end.

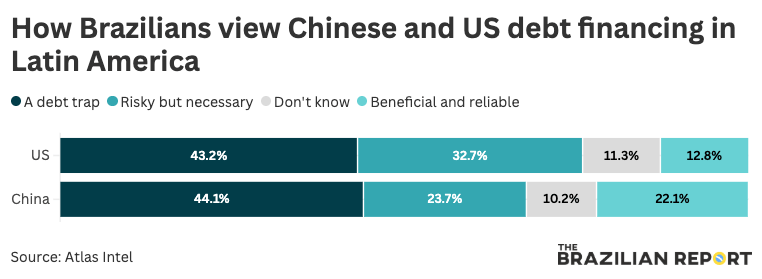

So while a majority support increased trade with both China and the United States, there is deep ambivalence about the long-term implications of such partnerships. Roughly 44% of Brazilians see Chinese loans to Latin America as a debt trap that undermines economic independence. A nearly identical share (43.2%) say the same about the US.

Still, 22% of Brazilians see Chinese financing as reliable and beneficial — against just 12% who say the same about American investments.

Meanwhile, nearly two-thirds of Brazilians are concerned about the ongoing US-China trade war. And 38% believe the rivalry could significantly harm Brazil’s economy. These anxieties transcend ideology and education levels, although younger and less affluent respondents tend to view China more favorably, while college-educated voters are more divided.

Politically, Lula has leaned into this realignment with rhetorical gusto. In Beijing, he compared his electoral victory to China’s Communist revolution. At home, he has pushed back strongly against American interference in Brazilian politics — especially after members of the US administration suggested sanctions against one of Brazil’s Supreme Court justices.

Still, Lula’s tone toward the United States has not been uniformly antagonistic. His administration has made overtures for deeper engagement with Washington and recently welcomed a temporary tariff truce between the two superpowers, a détente that could help stabilize global commodity markets.

Robert Kaplan, the American author and strategist, argued in an interview with Fortune that countries may be forced to choose between the two superpowers as China and the US grow further apart.

Brazilians, it seems, are similarly unwilling to choose. When asked which global bloc Brazil should align itself with, 44.2% chose the BRICS alliance. The US was the preferred partner for 36.9% of respondents, while just 4% favored aligning with China.

The preference appears to be for multipolar engagement, with BRICS seen as a vehicle for asserting national autonomy without becoming overly dependent on either superpower. Brazilians believe the country must pick deals, not sides.

This BRICS favor may be tested this week, as Rio de Janeiro hosts the bloc’s annual summit on Friday and Saturday.

2026 ELECTION

Eduardo Bolsonaro jockeys for his father’s legacy

Eduardo Bolsonaro was Brazil’s best-voted lawmaker in 2016. He thinks he might be presidential material — that is, if his dad says so. Photo: Nanacy Ayumi Kunihiro/Shutterstock

Eduardo Bolsonaro, the third-eldest son of former President Jair Bolsonaro, is angling to inherit his father’s political capital — and he is not being subtle about it.

In an interview with weekly magazine Veja, the congressman (who abandoned his legislative duties in March and is living in the US) suggested he could run for president in 2026. “Obviously, if it’s a mission given to me by my father, I’ll fulfill it,” he said. The move startled conservative allies, as multiple right-wing governors are jockeying to be the next standard bearer for Bolsonarism, as Jair Bolsonaro was declared ineligible for office until 2030 for electoral crimes — and could soon be convicted to serve a prison sentence for allegedly plotting a coup.

👉 Why it matters. Eduardo Bolsonaro is by no means an obvious choice. Valdemar Costa Neto, chairman of the Liberal Party, is said to favor Michelle Bolsonaro, the former first lady, as a more bankable candidate (her connections to evangelical churches are considered political gold by Costa Neto).

Governor Tarcísio de Freitas of São Paulo, meanwhile, is the preferred option among business leaders, centrist parties and right-wing moderates.

But there is no love lost between Eduardo, Michelle and Freitas — and the former president’s son appears determined to block them from claiming his father's political inheritance. According to close allies, he believes only Bolsonaro’s sons should carry the family brand in a presidential contest.

A May simulation by Atlas Intel showed Freitas narrowly outperforming Michelle in runoff scenarios against President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, while Eduardo’s name was not tested. These early numbers have limited predictive value — the 2026 vote is still nearly 18 months away, and most voters are not yet focused on the race — but they can shape political decisions and strategies.

While his father is facing a likely Supreme Court conviction for trying to stage a coup, Eduardo faces his own legal issues. He was recently added to a Supreme Court investigation into attempts to coerce or obstruct justice by lobbying US lawmakers to criticize Brazil’s judiciary.

For now, Jair Bolsonaro remains the gravitational center of Brazil’s right, even from the sidelines. A nod from the former president would almost certainly guarantee any candidate a place in a runoff against Lula, and no would-be successor should expect his blessing without fully committing to granting coup-plotting amnesty to Bolsonaro and his acolytes.

QUICK CATCH-UP

🛬 Brazil’s aviation regulator has suspended all airmail by the national postal service, Correios, starting June 4, after inspections found failures to screen for hazardous materials. In November, lithium batteries sparked a fire in a plane landing at Guarulhos airport, Brazil’s busiest. The suspension may be lifted if the company addresses the violations.

🤔 Inside Congress, allies of former President Jair Bolsonaro are pushing to broaden the definition of terrorism and impose harsher penalties. Outside, they are aiding a convicted would-be bomber who tried to attack Brasília airport in 2022 in a plot to disrupt President Lula’s inauguration. George Washington de Sousa, who planted a fuel truck rigged with explosives at the capital’s airport in a bid to prevent Lula’s inauguration, has since been released and is being supported by a pro-Bolsonaro network.

🔐 One in four Brazilians fell victim to banking fraud in 2024, according to a new report by Idwall. The number of cases was 3.6 times higher than in 2023, with card cloning accounting for over 20 percent of incidents.